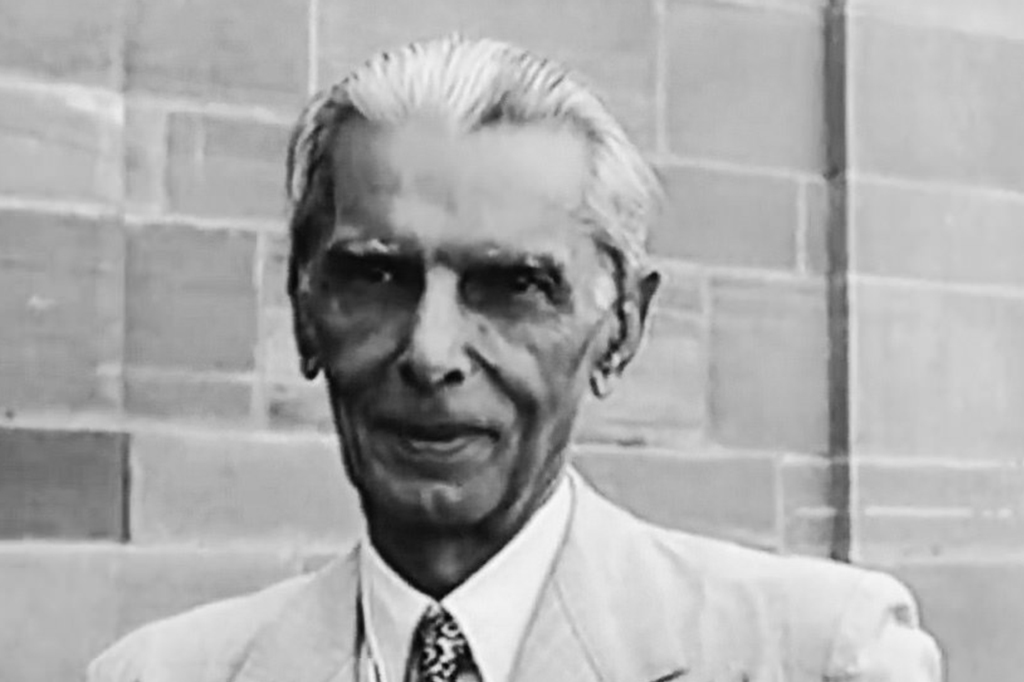

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Urdu) محمد علی جناح : born in 25 December 1876 He was a lawyer, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until Pakistan’s independence on 14 August 1947, and then as Pakistan’s first Governor-General until his death. He is revered in Pakistan as Quaid-e-Azam (Urdu: قائد اعظم, “Great Leader”) and Baba-i-Qaum (بابائے قوم, “Father of the Nation”). His birthday is considered a national holiday in Pakistan.

Jinnah’s father Jinnahbhai Poonja (born 1850) was the youngest of three sons. He married a girl Mithibai with the consent of his parents and moved to the growing port of Karachi. There, the young couple rented an apartment on the second floor of a three-storey house, Wazir Mansion. The Wazir Mansion has since been rebuilt and made into a national monument and museum owing to the fact that the founder of the nation, and one of the greatest leaders of all times was born within its walls.

On December 25, 1876, Mithibai gave birth to a son, the first of seven children. The fragile infant who appeared so weak that it weighed a few pounds less than normal. But Mithibai was unusually fond of her little boy, insisting he would grow up to be an achiever.

Officially named Mahomedali Jinnahbhai, his father enrolled him in school when he was six—the Sindh Madrasatul-Islam; Jinnah was indifferent to his studies and loathed arithmetic, preferring to play outdoors with his friends. His father was especially keen towards his studying arithmetic as it was vital in his business. By the early 1880s’ Jinnahbhai Poonja’s trade business had prospered greatly. He handled all sorts of goods: cotton, wool, hides, oil-seeds, and grain for export and Manchester manufactured piece of goods, metals, refined sugar imports into the busy port. Business was good and profits were soaring high.1

In 1887, Jinnahbhai’s only sister Man Bai came to visit from Bombay. Jinnah was very fond of his Aunt and vice versa. She offered to take her nephew with her in order to give him a chance of better education at the metropolitan city, Bombay, that was much to his mother’s dismay who could not bear the thought of being separated from her undisputedly favorite child. Jinnah joined Gokal Das Tej Primary School in Bombay.

For His spirited brain rebelled inside the typical Indian primary school which relied mostly on the method of learning by rote. He remained in Bombay for only six months, returned to Karachi upon his mother’s insistence and joined the Sind Madrassa. But his name was struck off as he frequently cut classes in order to ride his father’s horses. He was fascinated by the horses and lured towards them. He also enjoyed reading poetry at his own leisure. As a child Jinnah was never intimidated by the authority and was not easy to control.

He then joined the Christian Mission High School where his parents thought his restless mind could be focused. Karachi proved more prosperous for young Jinnah than Bombay had been. His father’s business had prospered so much by this time that he had his own stables and carriages. Jinnahbhai Poonja’s firm was closely associated with the leading British managing agency in Karachi, Douglas Graham and Company. Sir Frederick Leigh Croft, the general manager of the company, had a great influence over young Jinnah, which possibly lasted his entire life.

Jinnah looked up to the handsome, well dressed and a successful man. Sir Frederick liked Mamad (Jinnah’s childhood name), recognizing his extreme potential, he offered him an apprenticeship at his office in London.3 That kind of opportunity was the dream of all young boys of India, but the privilege went to only one in a million. Sir Frederick had truly picked one in a million when he chose Jinnah.

References

- 1.Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1984) P.5

- 2.Ibid. p.6.

- 3.Ibid. p.7.

FIRST WEDDING

When Jinnah’s mother heard of his plans of going to London for at least two years, she objected strongly to such a move. For her, the separation for six months while her dear son had been in Bombay was testing, she said that she could not bear this long never ending stretch of two to three years. Maybe the intuition told her that separation would be permanent for her and that she would never see her son again.

After much persuasion by adamant Jinnah, she consented, but with the condition that Jinnah would marry before he went to England. ‘England’, she said ‘was a dangerous country to send an unmarried and handsome young man like her son. Some English girl might lure him into marriage and that would be a tragedy for the Jinnah Poonja family.’1 Realizing the importance of his mother’s demand, Jinnah conceded to it.

Mithibai arranged his marriage with a fourteen-year-old girl named Emibai from the Paneli village. The parents made all wedding arrangements. The young couple quietly accepted the arranged marriage including all other decisions regarding the wedding like most youngsters in India at that time.

‘Mohammad was hardly sixteen and had never seen the girl he was to marry.’ Jinnah’s sister Fatima reports. ‘Decked from head to foot in long flowing rows of flowers…, he marched in a procession from his grand-father’s house to that of his father-in-law, where sat his fourteen year old bride, Emi Bai, dressed in expensive new clothes, heavily bejewelled, her hands spotted with henna, her face and clothes heavily sprinkled with costly itar.”2

The ceremony took place in February 1892; it was a grand affair celebrated by the whole village. Huge lunch and dinner parties were arranged and all were invited. It was the wedding of Jinnahbhai Poonja and Mithibai’s first son and the entire village was lured into the festivity.

During their prolonged stay in Paneli, Jinnahbhai’s business began to suffer. It was needed for him to return but he wished to take his family and his son’s new bride along with him. The bride’s father however, was adamant that Jinnah should stay for the customary period of one and a half month after marriage. The two families, newly bonded in marriage, were about to break into a quarrel until the intervention of young Jinnah. He spoke to his father-in-law in privacy and informed him that it was necessary for his father to return immediately along with his family. He gave the option of either sending the young bride back with him or sending her later when he would go to England for two or three years. Jinnah’s persuasive power, coupled with extreme politeness was evident even at that age. Emi Bai’s father consented to send his daughter, and the wedding party returned to Karachi.

How Jinnah felt about that marriage and his new bride was uncertain, he had little time to adjust since he sailed off to England soon after his return. Upon their return to Karachi, his young bride observed the custom of covering her face with her headscarf in front of her father-in-law. But the progressive Jinnah soon encouraged her to discard this practice.

He studied in the Christian Mission School until the end of October in order to improve his English before his voyage that was planned by November 1892, though some argue that he sailed in January 1893. He was not to see his young bride ever again as she died soon after he sailed from India.

References

- 1.Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1984) P.7.

- 2.Fatima Jinnah, My Brother, (Karachi: Quaid-i-Azam Academy, 1987) pp.64-5.

SECOND WEDDING

Quaid had best and close relations with Parsi community. He used to visit Sir Dinshaw Petit, a Parsi businessman; Sir Dinshaw had a daughter, Ruttie who was convinced by Jinnah’s qualities of head and heart. She started taking interest in Jinnah. Her interest converted into love during their summer vacation to Darjeeling in April 1916.1 When Sir Dinshaw came to know their love affair, he forbade Ruttie ever to see Jinnah again. Then he sought legal remedies to prevent their marriage. The couple silently, patiently, passionately waited till Ruttie attained her majority at 18.2 Jinnah married Ruttie on Friday, April 19, 1918. She had converted to Islam. None of Ruttie’s relatives attended her wedding. The Raja of Mahamudabad gave Ruttie a ring as a wedding gift. They spent their honeymoon at Nainital. Maulana Muhammad Hassan Najafi on behalf of Ruttie and Haji Muhammad Abdul Hashim Najafi on behalf of Jinnah signed the Nikah document/Register. Their wedding took place according to Shia Isna Ashri doctrine.3 At about midnight (August 14-15, 1919) their only child, a daughter named Dina was born in London. The relations between Jinnah and Ruttie were smooth and pleasant. But in January 1928 after their return from All India Muslim League Annual Session at Calcutta, Ruttie and Jinnah started living separately. Khawaja Razi Haider writes: “it seems that Ruttie Jinnah, young and lively as she was, wanted a glamorous life—a life full of joy and excitement but unfortunately, Jinnah had no time to spare due to his political preoccupation”.4 She left the house on Mount Pleasant Road and gone to live in the Taj Mahal Hotel. During her stay at Taj Mahal, Ruttie’s health was deteriorating day by day. She decided to go abroad just for a change of climate and treatment. She sailed for Paris on April 10, 1928 with her mother. On May 5, 1928, Jinnah left for London. Chaman Lal, a friend of Jinnah who came from Paris to Ireland informed Jinnah about Ruttie’s health. She was delirious with “a temperature of 106 degrees”.5 He reached Paris in two days, and spoke with Lady Petit. Ruttie remained under treatment for over a month in Paris. Ruttie returned to Bombay alone. She had fallen ill again. On 19th February 1929, she became unconscious and remained so until the next day, the February 20, 1929, which was her twenty-ninth birthday. She breathed her last the same fateful day. When Ruttie died, Jinnah was in Delhi. On February 22, Jinnah reached Bombay. Describing Kanji Dwarkdas, Khawaja Razi Haider writes, “When Ruttie’s body was being lowered down the grave, Jinnah was not able to control his emotions. He broke down and wept like a child.”6

Apparently there was a separation between the couple but Ruttie’s love for Jinnah was never ending. She wrote to him in October 1928 while coming back from Paris to India. She wrote, “Darling thank you for all you have done…. Darling I love you—I love you…. I only beseech you that our tragedy, which commenced with love, should also end with it.”7

References

- 1.Khwaja Razi Haider, Ruttie Jinnah: the story, Told and Untold (Karachi: Pakistan Study Centre, University of Karachi, 2004) p. 25.

- 2.Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1984) p. 52.

- 3.Khawaja Razi Haider, op. cit. p. 34.

- 4.Ibid. p. 139.

- 5.Ibid. pp. 140-142.

- 6.Ibid. p. 149.

- 7.Ibid. pp. 143-144.

A JOUNERY TO LONDON

Jinnah barely sixteen sailed for London in the midst of winter. When he was saying goodbye to his mother her eyes were heavy with tears. He told her not to cry and said that he will return a great man from England and not only she and the family but the whole country will be proud of him. This was the last time he saw his mother, for she, like his wife, died during his three and a half year stay in England.

The youngest passenger on his own, was befriended by a kind Englishman who engaged in conversations with him and gave tips about life in England. He also gave Jinnah his address in London and later invited to dine with his family as often as he could.

His father had deposited enough money in his son’s account to last him for the three years of the intended stay. Jinnah used that money wisely and was able to have a small amount left over at the end of his three and a half year tenure.

When he arrived in London he rented a modest room in a hotel. He lived in different places before he moved into the house of Mrs. F. E. Page-Drake as a houseguest at 35 Russell Road in Kensington. This house now displays a blue and white ceramic oval saying that the ‘founder of Pakistan stayed here in 1895.1

Mrs. Page- Drake, a widow, took an instant liking to the impeccably dressed well-mannered young man. Her daughter however, had a more keen interest in the handsome Jinnah, who was of the same age of Jinnah. She hinted her intentions but did not get a favorable response. As Fatima reflects, “he was not the type who would squander his affections on passing fancies”.2

On March 30, 1895 Jinnah applied to Lincoln’s Inn Council for the alteration of his name the from Mahomedalli Jinnahbhai to Mahomed Alli Jinnah, which he anglicized to M.A. Jinnah. This was granted to him in April 1895.

Though he found life in London dreary at first and was unable to accept the cold winters and gray skies, he soon adjusted to those surroundings, quite the opposite of what he was accustomed to in India.

After joining Lincoln’s Inn in June 1893, he developed further interest in politics. He thought the world of politics was ‘glamorous’ and often went to the House of Commons and marveled at the speeches he heard there. Although his father was furious when he learnt of Jinnah’s change in plan regarding his career, there was little he could do to alter what his son had made his mind up for. At that point in life Jinnah was totally alone in his decisions, with no moral support from his father or any help from Sir Frederick. He was left with his chosen course of action without a pillar of support to fall back upon. It would not be the only time in his life when he would be isolated in a difficult position. But without hesitation he set off on his chosen task and managed to succeed.

References

- 1. Fatima Jinnah, My Brother, (Karachi: Quaid-i-Azam Academy, 1987) p-72.

- 2.Ibid., p. 76.

THE THEATRE

During his stay in London, Jinnah frequently visited the theatre. He was mesmerized by the acting, especially those of the Shakespearean actors. His dream was to ‘play the role of Romeo at the Old Vic.’ It is unclear when his passion for theatre was unfurlled, perhaps it occurred while watching the performances of barristers, ‘the greatest of whom were often spell-binding thespians’. This was no passing phase in life, but an obsession which continued even in his later years. Fatima reminiscences, ” Even in the days of his most active political life, when he returned home tired … he would take a play of Shakespeare and quietly read it in his bed”.1

With a theatrical prop, his monocle, always in place in court, he performed like an actor on stage in front of the judge and jury. With dramatic interrogations and imperious asides, he was regarded as a born actor.

After being enrolled to the Bar he went with his friends to the Manager of a theatrical company who asked him to read out pieces of Shakespeare. On doing so, he was immediately offered a job. He was exultant and wrote to his parents about his newfound passion.

He said, ‘I wrote to them that law was a lingering profession where success was uncertain; a stage career was much better, and it gave me a good start, and that I would now be independent and not bother them with grants of money at all.” My father wrote a long letter to me strongly disapproving of my project; but there was one sentence in his letter that touched me most and which influenced a change in my decision: “Do not be a traitor to the family.” I went to my employers and conveyed to them that I no longer looked forward to a stage career. They were surprised, and they tried to persuade me, but my mind was made up. According to the terms of the contract I had signed with them, I was to have given them three months notice before I quitting. But you know, they were Englishmen, and so they said: “Well when you have no interest in the stage, why should we keep you, against your wishes?”2

The signed contract is proof that how important the stage career was for Jinnah at that time, it was possibly his first love. His father’s letter had dissuaded him for the time being, disheartened and dejected, he had consented to his wish. But it was probably the last time he changed his mind after seriously devoting it to something.

References

- 1.Fatima Jinnah, My Brother, (Karahci: Quaid-i-Azam Academy, 1987) p. 80.

- 2.Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1984) pp. 14-5.

LIFE IN LONDON

Jinnah left for England in January 1893, landed at Southampton, catching the boat train to Victoria Station. “During the first few months I found a strange country and unfamiliar surroundings,” he recalled. “I did not know a soul and the fogs and winter in London upset me a great deal”.1 He worked at Graham’s for a while surrounded by stacks of account books he was expected to copy and balance. His father had deposited enough money in his account in a British bank to last for three years of his stay in London. He took a room as houseguest in a modest three-story house at 35 Russell Road in Kensington.

He arrived in London in February 1893 and after two months he left Graham’s on April 25 of that year to join Lincoln’s Inn, one of the oldest and well reputed legal societies that prepared students for the Bar. On June 25, 1893, he embarked on his study of the law at Lincoln’s Inn. His quest for general books especially on politics and biographies led him to apply to the British Museum Library and he became a subscriber of the Museum Library. The two years of “reading” apprenticeship that he spent in barrister’s chambers was the most important element in Jinnah’s legal education. He used to follow his master’s professional footsteps outside the chambers as well. When Jinnah landed at Southampton, it was the peak of British power and influence in the world. The Victorian era was about to end and a new economic order was struggling to be born. Young Jinnah was greatly affected by the life in what was then called, “the greatest capital of the world”, where people had more freedom to pursue what they believed in. Apart from his upbringing according to the traditions and ethics of a religious family, the Victorian moral code not only colored his social behavior but also greatly affected his professional conduct as a practicing lawyer. Jinnah’s political beliefs and personal demeanor as a public man in India for four decades clearly indicate that his training, education and life in London profoundly influenced his way of life. It was that influence and training that helped him a great deal in presenting the most important case of his life and eventually led him to win that case a free country for the Muslims of the subcontinent.

In London, he received the tragic news of the death of his mother and first wife. Nevertheless, he completed his formal studies and also made a study of the British political system by frequently visiting the House of Commons. He was the youngest student ever to be called to the Bar.

It was in London that he acquired love of personal freedom and national independence. Inspired by the British democratic principles and fired by a new faith in supremacy of law, liberalism and constitutionalism became twin tools of Jinnah’s political creed which he daringly but discreetly used during the rest of his life. He was greatly influenced by the liberalism of William E. Gladstone, who had become prime minister for the fourth time in 1892.

Jinnah also took keen interest in the political affairs of India. He was extremely conscious of the lack of a strong voice from India in the British Parliament. So, when the Parsi leader Dadabhai Naoroji, a leading Indian nationalist, ran for the British Parliament, it created a wave of enthusiasm among Indian students in London. Naoroji became the first Indian to sit in the House of Commons. Naoroji’s victory acted as a stimulus for Jinnah to lay the foundation of the “political career” that he had in his mind.

Jinnah was a marvelous speaker and was recognised as a balanced and reasoned debater. His power of speech had an ability to mesmerise the audience.

References

- 1.Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan, (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1984) p. 8.

QUAID AS A LAWYER

Having qualified as a barrister in England and having made his mark in India, Jinnah’s name could be justly added to the ‘list of great lawyers’ academically linked to Lincoln’s Inn. Jinnah practiced both law and politics for half a century; he made a fortune as an advocate and earned glory and gratitude of prosperity as leader of the Indian Muslims. When Jinnah left the shores of free England and voyaged to subject India in 1896, he had perhaps no idea that, one day, he would be obliged by the erstwhile Hindu leaders to make history and his biggest brief would be to win the case of the Indian Muslims for a separate homeland.

LIFE IN BOMBAY

Jinnah left London for India in 1896. He decided to go to Bombay after a brief stay in Karachi. He opted for Bombay because it offered scope for the exercise of his legal faculties and ground for his political ambitions. Bombay had the brightest constellation of India’s lawyer-politicians, at that time. Ranade, Badruddin Tyabji, Gandhi, Tilak, Gokhale, Cowasji, Dadabhoy Naoroji, Bholabhai Desai, Wacha, Nariman and many more renowned men were based in Bombay.

He was enrolled as a barrister in Bombays’ high court on August 24, 1896. He took up lodgings in Room No.110 of Apollo Hotel. Father’s business had suffered serious losses by then, and he could hardly get any brief for a year or so but he never stopped helping the poor and needy, even in his precarious financial position. In a letter to the Times of India, Bombay, the June 10, 1910 issue, he appealed to the well-off section of the Muslim Community in Bombay to aid a Muslim orphanage in the city. He donated a handsome amount to the orphanage at a time when his practice was not even flourishing. By 1900, he was introduced to Bombay’s acting advocate-general, John Molesworth McPherson, and was invited to work with him in his office. But soon he succeeded in crossing all the hurdles to become a leading lawyer of India. He won many famous cases through powerful advocacy and legal logic.

In politics, he admired Dadabhai Naoroji and another brilliant Parsi leader Sir Pherozeshah Mehta. It was Pherozeshah Mehta, who entrusted him to defend him in the famous Caucus Case. Jinnah hit the headlines in this case; it was remarkable how a 62-year-old statesman of the Congress and an eminent lawyer had entrusted his defence to a young Muslim barrister.

Jinnah appeared in the annual session of the All India Congress, Calcutta, 1906. Dadabhai Naoroji presided over the session with Jinnah serving as his secretary. In his speech Dadabhai called the partition of Bengal a bad blunder for England and addressed the growing distance between the Hindus and the Muslims in the aftermath of partition. He called for a thorough political union among the Indian people of all creeds and classes. To him, the thorough union, therefore, of all the person for their emancipation was an absolute necessity. He viewed that they must sink or swim together. He told them that all efforts would go in vain without union.1

Jinnah reiterated this call for national unity at every political meeting he attended in those years, and he emerged as true Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. He met India’s poetess Sarojini Naidu at that Calcutta annual session of Congress, who was instantly captivated by the stunning appearance and rare temperament of India’s rising lawyer and upcoming politician.

References

- 1.A. M. Zaidi, ed., The Encyclopedia of Indian National Congress, 1906-1910, Vol. V, (New Delhi: Indian Institute of Applied Political Research), pp. 116-39.

THE STATESMAN

If Jinnah’s stay in London was the sowing time, the first decade in Bombay, after return from England, was the germination season, the next decade (1906-1916) marked the vintage stage; it could also be called a period of idealism, as Jinnah was a romanticist both in personal and political life. Jinnah came out of his shell, political limelight shone on him; he was budding as a lawyer and flowering as a political personality. A political child during the first decade of the century, Jinnah had become a political giant before Gandhi returned to India from South Africa. Jinnah’s fascination with the world of politics started from his early days in London. He was very impressed by Dadabhai, a Parsi from Bombay. Upon returning to India, Jinnah entered the world of politics as a Liberal nationalist and joined the Congress despite his father’s fury at his abandoning the family business. The 20th annual session of the Congress in December 1904, was the first attended by Jinnah in Bombay. It was presided over by Pherozshah Mehta of whom Jinnah was a great admirer. Mehta suggested that two of his chosen disciples be sent to London as Congress deputies to observe the political arena at that time. His choices for the job were M.A Jinnah and Gopal Krishna Gokhale whose wisdom and moderation the former also admired.

This was the story about our Great leader Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, A small tribute to our Great leader. Copied If anything goes wrong please let me know via comments. I request to every reader please pray for Pakistan and Pakistan’s people, and try play your part as a Pakistani against corruption and today’s corrupt leaders.